Following on from previous years of foraging studies in the Charleston area, during the 2023 season we carried out a pilot study at Camerons Beach, south of Greymouth, tracking the foraging paths of three blue penguins during chick guard stage, when one adult remains to guard and the other goes to sea to forage. Our plan was to carry out a more extensive study in 2024. This is the first time we have undertaken any study at the Camerons Beach colony and we plan to continue and expand this project in the next few years.

We hope this will give us an insight into the foraging areas and patterns of our local penguins in this more residential area of the West Coast.

Two important reasons for carrying out a foraging study are firstly, finding out what determines where the penguins are going to find their food source and what might affect their foraging behaviour and success. Sea surface temperatures? Chlorophyll amounts? Different marine conditions? And secondly, to understand and map where penguins go, which will help us contribute to marine science and spatial planning, to discuss with fisheries and, overall, help us to protect our wildlife and the marine ecosystems they rely on.

We have carried out foraging studies in the past at Charleston close to the Nile River in previous years and it will be interesting to see the results of this year and make comparisons.

Read about these previous studies here.

The stormy weather of 2024 Spring, with the relentless driving rain and high winds, started our foraging study off to a shaky start this season. However, despite the obstacles, scientist Dr Thomas Mattern, Masters student Patrick Daugherty and I managed to find a long enough break in the weather to deploy our first GPS loggers at Camerons Beach during the first week of September.

We successfully managed to deploy three loggers on penguins in incubation stage. Kororā usually take turns to incubate their eggs for a period of approximately 36 days, sometimes swapping every couple of days, sometimes staying on their eggs for up to 7-8 days and then swapping. Unfortunately, after six days, we had to retrieve the loggers, eliminating the risk of losing the valuable devices. Disappointingly, we received no data from this deployment as all three logger birds stayed in their nests for the entire six day period. This in itself could give us some information about the colony, as all the three burrows were within a few metres, posing the question, do they actually work together, perhaps coming in as a group, known as rafting up in this colony? Something we haven’t seen. Are they sharing patterns of behaviour?

This experience also shows how field work with little penguins very often doesn’t go to plan. We redeployed another three loggers on different nests, a week later, and all birds went out this time.

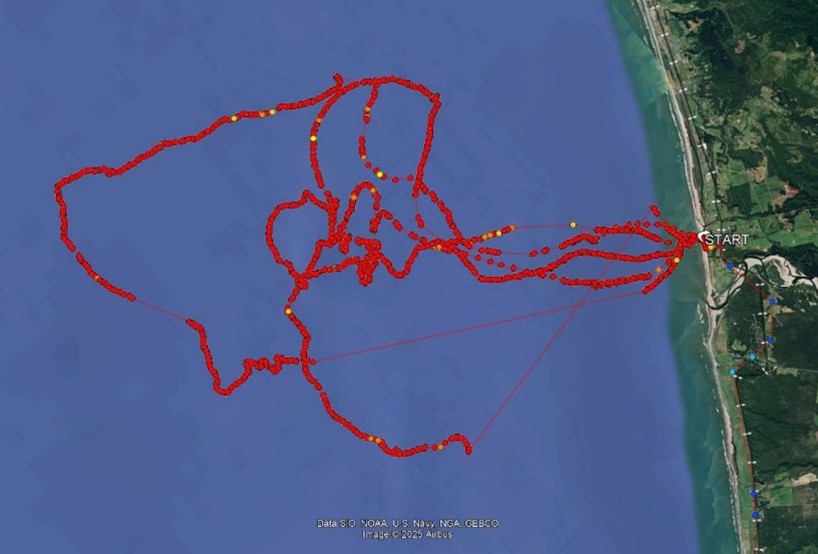

The above map shows the journeys of an adult nesting in the north of the Camerons colony during incubation stage. The penguin carried a logger from 11/9/24 to the 23/9/24. This bird had also stayed in its nest for six days and when we went to retrieve the logger it had decided to leave, so we were slightly anxious about the retrieval. We had to check the nest each day to check for the bird’s return. The penguin made 3 trips that were recorded. This bird weighed 1120g on deployment and 1060g on retrieval. The data for this penguin during these trips is shown below.

| Summary data: | |

| Dives made: 799 | Max dive depth: 40.8 metres |

| Mean dive time: 31.47 seconds | Mean home range: 17.9 km |

| Max dive time: 79 seconds | Max home range: 24.8 km |

| (longest dive recorded of all 2024 data) | Distance travelled: 63.5 km |

| Mean dive depth: 10.9 metres |

The second deployment round happened mid-October, three more loggers were put on penguins on chick guard stage.

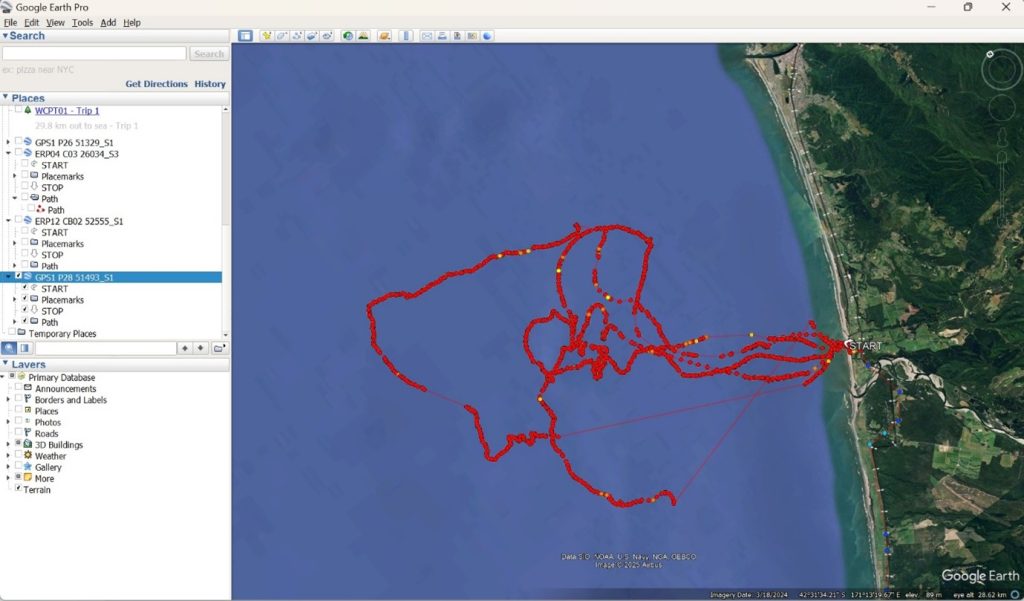

This adult, again breeding at the north end of the colony, made three recorded trips between 15/10/24 and 21/10/24 during chick guard stage. The penguin weighed 920g on deployment and 1040g on retrieval.

| Summary data: | |

| Dives made: 1136 | Max dive depth: 30.2 metres |

| Mean dive time: 27.22 seconds | Mean home range: 11.4 km |

| Max dive time: 30.2.seconds | Max home range: 20.1 km |

| Distance travelled: 52 km | Mean dive depth: 10.4 metres |

We are very fortunate to have Master’s student at Otago University, Patrick Daugherty, to analyse the data for us as part of his Master’s project. His project includes comparing our penguins and data with those of a similar community project in Taranaki. It will include relating foraging data to marine parameters. We hope to see some of his findings in early 2026, including data from the coming breeding season.

In the meantime, we can have a look at some simple foraging statistics, such as number of dives and dive times during chick guard stage and it appears that the birds had to work harder in 2024. The mean number of dives in 2023 was 1,125 versus 1,296 dives in 2024. There were longer dive times in 2024: mean dive times of 28.4 seconds in 2024, compared to 19.6 seconds in 2023.

At the same time, they seemed to forage closer to home in 2024: travel distance 52.0 km in 2024 compared to 76.8 km in 2023 and home range of 10.5 km in 2024 compared to 17.3 km in 2023.

So during the 2024 breeding season, penguins had more dives per trip, longer dive times, and travelled less far than in 2023.

What these observations and statistics mean in the context of environmental variables, is what Patrick will be looking into in the future, with more data and further seasons. We are just at the start of this kind of monitoring at Camerons Beach and only after a few years of data collection, will hope to understand which environmental factors influence foraging behaviour as well as breeding success.

What we can do for now is note observations from the season and start asking questions for the future data to be collected, such as the difference in the foraging area for penguins from the north part of the colony to the south – are the birds from the north foraging in different zones? Does it make a difference? Did it have anything to do with the starvation and issues in the northern nest boxes that we saw?

This season, the south side birds all bred at the same time and all fledged in a similar window. They were all very healthy weight birds and chicks, no dramas on the south side! Whereas the north side was the location of the particularly early breeders (for the colony’s trend this season), late breeders (again compared to the colony’s trend this season), a failed attempt, one dead adult during post guard chick stage that died in the nest box and multiple chick deaths, evidence of ticks and tape worm, one chick with possible avian malaria and avian pox (although all later in the season).

Are these linked to foraging habits and areas or coincidence? Are they simply a regular part of a penguin colony?

We look forward to this coming season to give us some more insight, and add to the data set, as we cannot read too much into our small amount of data just yet. However, we have confirmed that Camerons is an excellent study site and we are keeping in close contact with the Guardians of Paroa Taramakau Coastal Area Trust as we go. We can also use the data we have to become more informed about our local penguins and share this with the community and schools to raise greater awareness of these fascinating birds, who are an essential sentinel of the ocean for us. Kororā can act as indicators of the health of the marine ecosystems, potentially letting us know about the presence of pollutants, pathogens, local fishing activity, climate change, as they are often sensitive to these changes. Our work tracking and monitoring our penguins can help inform environmental risk assessments, policies, plans and consents, and thereby help protect our local wildlife and coastal environment.

Watch this space…..

WCPT Ranger, Lucy Waller

While materials were chosen that would stand up to the harsh coastal conditions, those same coastal conditions are conducive to plant growth! Occasional checks of the fences have been carried out by volunteers and rangers so that any maintenance needs can be identified and remedied. The never-ending need for maintenance is managing the vegetation that can grow through the fence, for example gorse, blackberry and hydrangea, pushing it to breaking point in places, or flop over causing damage from the weight of rank grass, rushes and weeds such as montbretia.

Volunteers recently spent a few hours tidying up the main fence along Woodpecker Bay north of Punakaiki so a big shout out to them - thank you Fiona, Jony, Reef, Katrina, Mandy, Marty, Teresa and Deb! Flax had been pressing down on the fence, but now the fence has been freed up by these wonderful volunteers - and they picked up a fair bit of rubbish too.

While materials were chosen that would stand up to the harsh coastal conditions, those same coastal conditions are conducive to plant growth! Occasional checks of the fences have been carried out by volunteers and rangers so that any maintenance needs can be identified and remedied. The never-ending need for maintenance is managing the vegetation that can grow through the fence, for example gorse, blackberry and hydrangea, pushing it to breaking point in places, or flop over causing damage from the weight of rank grass, rushes and weeds such as montbretia.

Volunteers recently spent a few hours tidying up the main fence along Woodpecker Bay north of Punakaiki so a big shout out to them - thank you Fiona, Jony, Reef, Katrina, Mandy, Marty, Teresa and Deb! Flax had been pressing down on the fence, but now the fence has been freed up by these wonderful volunteers - and they picked up a fair bit of rubbish too.

Volunteer Natassja Savidge has offered to check and help maintain the Hokitika penguin protection fence and joined Ranger Lucy Waller and Manager Inger Perkins in May to inspect the length of the fence. Some minor issues were found but the main finding was the extent of the vegetation growth that was damaging the fence in places. Big thanks to Natassja!

Volunteer Natassja Savidge has offered to check and help maintain the Hokitika penguin protection fence and joined Ranger Lucy Waller and Manager Inger Perkins in May to inspect the length of the fence. Some minor issues were found but the main finding was the extent of the vegetation growth that was damaging the fence in places. Big thanks to Natassja!